经济民族主义 发表评论(0) 编辑词条

简介 编辑本段回目录

经济民族主义在次贷危机中抬头

经济民族主义在次贷危机中抬头从宏观上看,现代民族国家仍是各种资源和财富分配的基本单位,在资源有限并且紧缺的世界体系中,全球竞争主要是国与国之间的经济竞争,个人和团体最大的现实福利单元在相当时期内是仍然是民族国家。基于这样的认识,经济民族主义主张国家把追求更多的超额利润当作最重要的政治目标之一。一般而言,它对激进的全球化观念持怀疑甚至否定的态度,认为不应该为抽象的世界福利而牺牲本国利益;相反,它往往认同一个民族国家经济地位的上升要以牺牲另一个民族国家经济为代价这样的残酷现实。如果经济民族主义偶尔也赞同或直接介入全球化,那是因为它把全球化视为实现本民族国家的手段。

出发点 编辑本段回目录

经济民族主义的出发点是民族国家在世界经济体系中的相对获益而不是全球的绝对获益,它深切关注民族国家整体在世界政治经济体系中的地位,特别是由民族经济竞争力决定的民族的长期发展趋势,而不是世界的共存共荣。

率先杜绝经济民族主义经济民族主义最显著地体现在银行业。在法国和英国,政治家们将纳税人的钱投向出现问题的银行,并要求银行更多地对国内发放贷款。然而银行却减少了贷款,冻结了大部分资金转移。监管层面也以本国利益为出发点考虑问题。瑞士在政策上向国内贷款有所倾斜,而对国外贷款全额计入银行资本折算。

范围 编辑本段回目录

比如在法国,“经济民族主义”的另一种说法“经济爱国主义”已经成为前总理德维尔潘的口头禅。法国和卢森堡已中止了英国米塔尔钢铁公司收购法国的阿赛罗钢铁企业,以及法国和西班牙政府阻滞意大利和德国公司的“恶意”收购等。而在号称自由贸易大本营的美国,我们就见到美国国会否决阿联酋迪拜港口公司控制美国六城市港口经营权。至于中海油收购美优尼科公司遭美国政府的粗暴干预,以及美国国务院以国家安全为名对联想集团与美国政府签署的电脑销售合同提出的诸多限制措施,更是令我们记忆深刻。

在中国 编辑本段回目录

在2007年,对于中美两国和全球经济而言,一个紧迫问题就是中国需要更加灵活的汇率政策。中国正在寻求更加市场化的汇率机制,2006年,人民币已经升值6%,但是这一速度还不足以缓解中国的贸易盈余、国内经济的不平衡和来自外汇市场的压力。

在中国的通货膨胀风险正在上升之际,增加人民币的弹性显得尤其重要。增加人民币的弹性会使得中国的中央银行可以利用货币政策来保持中国的金融和价格稳定。正如温家宝总理所强调的,中国必须采取全面措施以控制通货膨胀、日益增大的资产泡沫以及过热的经济。

在中美关系中,人民币汇率问题已经成为引起中国竞争更多担忧的焦点。在全球化和各国经济越发紧密融合的时候,一些国家担心外国日益强大的竞争力会通过贸易或者投资给本国经济带来影响,这也助长了一种经济民族主义和保护主义情绪。

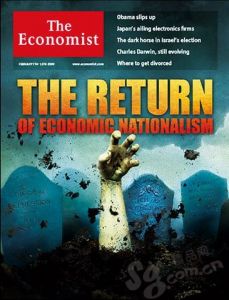

经济民族主义回潮 编辑本段回目录

1929到1934年,美国的《斯穆特·哈里斯法案》使全球贸易总额下降了三分之二,这项贸易保护主义的施行让所有的国家勒紧腰带控制进口。七十多年以后,不管是在达沃斯,还是在美国国会,全世界一致紧盯美国,看看它是不是会把经济危机变作新的借口,再一次为美国保驾护航。

经济民族主义致力于将就业机会与资本限制在本国之内,一旦得逞,将会把经济上的危机扩散到政治层面,使整个世界陷入萧条。如果不能马上遏制其发展,后果无疑将是灾难。《经济学人》称,奥巴马必须向世界证明他已经准备就绪,如果他已经准备好了,那么就应当扼杀任何“购买美国产品”的条款。如果他还没有,那么无论是美国还是世界的其他地方都会陷入沉重的危机。

《经济学人》 The Economist 2009年2月刊原文:

MANAGING a crisis as complex as this one has so far called for nuance and pragmatism rather than stridency and principle. Should governments prop up credit markets by offering guarantees or creating bad banks? Probably both. What package of fiscal stimulus would be most effective? It varies from one country to the next. Should banks be nationalised? Yes, in some circumstances. Only the foolish and the partisan have rejected (or embraced) any solutions categorically.

But the re-emergence of a spectre from the darkest period of modern history argues for a different, indeed strident, response. Economic nationalism—the urge to keep jobs and capital at home—is both turning the economic crisis into a political one and threatening the world with depression. If it is not buried again forthwith, the consequences will be dire.

Trade encourages specialisation, which brings prosperity; global capital markets, for all their problems, allocate money more efficiently than local ones; economic co-operation encourages confidence and enhances security. Yet despite its obvious benefits, the globalised economy is under threat.

Congress is arguing about a clause in the $800 billion-plus stimulus package that in its most extreme form. would press for the use of American materials in public works. Earlier, Tim Geithner, the new treasury secretary, accused China of “manipulating” its currency, prompting snarls from Beijing. Around the world, carmakers have lobbied for support (see article), and some have got it. A host of industries, in countries from India to Ecuador, want help from their governments.

The grip of nationalism is tightest in banking (see article). In France and Britain, politicians pouring taxpayers’ money into ailing banks are demanding that the cash be lent at home. Since banks are reducing overall lending, that means repatriating cash. Regulators are thinking nationally too. Switzerland now favours domestic loans by ignoring them in one measure of the capital its banks need to hold; foreign loans count in full.

Governments protect goods and capital largely in order to protect jobs. Around the world, workers are demanding help from the state with increasing panic. British strikers, quoting Gordon Brown’s ill-chosen words back at him, are demanding that he provide “British jobs for British workers” (see article). In France more than 1m people stayed away from work on January 29th, marching for jobs and wages. In Greece police used tear gas to control farmers calling for even more subsidies.

Three arguments are raised in defence of economic nationalism: that it is justified commercially; that it is justified politically; and that it won’t get very far. On the first point, some damaged banks may feel safer retreating to their home markets, where they understand the risks and benefit from scale; but that is a trend which governments should seek to counteract, not to encourage. On the second point, it is reasonable for politicians to want to spend taxpayers’ money at home—so long as the costs of doing so are not unacceptably high.

In this case, however, the costs could be enormous. For the third argument—that protectionism will not get very far—is dangerously complacent. True, everybody sensible scoffs at Reed Smoot and Willis Hawley, the lawmakers who in 1930 exacerbated the Depression by raising American tariffs. But reasonable people opposed them at the time, and failed to stop them: 1,028 economists petitioned against their bill. Certainly, global supply-chains are more complex and harder to pick apart than in those days. But when nationalism is on the march, even commercial logic gets trampled underfoot.

The links that bind countries’ economies together are under strain. World trade may well shrink this year for the first time since 1982. Net private-sector capital flows to the emerging markets are likely to fall to $165 billion, from a peak of $929 billion in 2007. Even if there were no policies to undermine it, globalisation is suffering its biggest reversal in the modern era.

Politicians know that, with support for open markets low and falling, they must be seen to do something; and policies designed to put something right at home can inadvertently eat away at the global system. An attempt to prop up Ireland’s banks last year sucked deposits out of Britain’s. American plans to monitor domestic bank lending month by month will encourage lending at home rather than abroad. As countries try to save themselves they endanger each other.

The big question is what America will do. At some moments in this crisis it has shown the way—by agreeing to supply dollars to countries that needed them, and by guaranteeing the contracts of European banks when it rescued a big insurer. But the “Buy American” provisions in the stimulus bill are alarmingly nationalistic. They would not even boost American employment in the short run, because—just as with Smoot-Hawley—the inevitable retaliation would destroy more jobs at exporting firms. And the political consequences would be far worse than the economic ones. They would send a disastrous signal to the rest of the world: the champion of open markets is going it alone.

Barack Obama says that he doesn’t like “Buy American” (and the provisions have been softened in the Senate’s version of the stimulus plan). That’s good—but not enough. Mr Obama should veto the entire package unless they are removed. And he must go further, by championing three principles.

The first principle is co-ordination—especially in rescue packages, like the one that helped the rich world’s banks last year. Countries’ stimulus plans should be built around common principles, even if they differ in the details. Co-ordination is good economics, as well as good politics: combined plans are also more economically potent than national ones.

The second principle is forbearance. Each nation’s stimulus plan should embrace open markets, even if some foreigners will benefit. Similarly, financial regulators should leave the re-regulation of cross-border banking until later, at an international level, rather than beggaring their neighbours by grabbing scarce capital, setting targets for domestic lending and drawing up rules with long-term consequences now.

The third principle is multilateralism. The IMF and the development banks should help to meet emerging markets’ shortfall in capital. They need the structure and the resources to do so. The World Trade Organisation can help to shore up the trading system if its members pledge to complete the Doha round of trade talks and make good on their promise at last year’s G20 meeting to put aside the arsenal of trade sanctions.

When economic conflict seems more likely than ever, what can persuade countries to give up their trade weapons? American leadership is the only chance. The international economic system depends upon a guarantor, prepared to back it during crises. In the 19th century Britain played that part. Nobody did between the wars, and the consequences were disastrous. Partly because of that mistake, America bravely sponsored a new economic order after the second world war.

Once again, the task of saving the world economy falls to America. Mr Obama must show that he is ready for it. If he is, he should kill any “Buy American” provisions. If he isn’t, America and the rest of the world are in deep trouble.

附件列表

→如果您认为本词条还有待完善,请 编辑词条

词条内容仅供参考,如果您需要解决具体问题

(尤其在法律、医学等领域),建议您咨询相关领域专业人士。

0

同义词: 暂无同义词

关于本词条的评论 (共0条)发表评论>>

编辑实验

创建词条

编辑实验

创建词条